Writing for Taxation magazine, BKL tax partner David Whiscombe examines changes in the treatment of income from buy-to-let properties.

KEY POINTS

- After 6 April 2017, rental profits must be computed without including interest payments.

- A new tax reduction relief will apply under ITTOIA 2005, s 272A.

- Complications arise if the tax reduction relief cannot be used in the relevant year.

- Companies are not affected by the new rules.

It seems the government does not like the boom in buy-to-let. In particular, the chancellor looks askance at individuals taking advantage of low interest rates to hoover up properties that he would rather see acquired by owner-occupiers. The assertion that it is “not fair” that landlords obtain tax relief for interest but owner-occupiers do not bears not a moment’s serious consideration.

Nonetheless, clause 24 of the Finance Bill 2015/16 limits tax relief to the basic rate for interest on loans taken to acquire buy-to-let property.

The new rules operate by requiring in the first instance that profits are computed without regard to the relevant interest payments. This is achieved by inserting new ITTOIA 2005, s 272A. There is then a separate relief – a “tax reduction” – provided by new s 274A. This is calculated by reference to basic rate tax on an amount equal to the interest payments for which s 272A has denied relief.

The changes are phased in over three years starting from 6 April 2017, with the new rules applying to 25% of the relevant interest in the first years, 50% in the second and 75% in the third. They bite in full on all relevant interest payments from 6 April 2020. Although their impact is ameliorated by the delayed and phased introduction, the changes will affect the economics of some buy-to-let portfolios significantly.

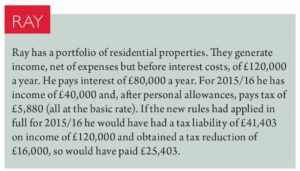

Because the effect of the new rules is merely to restrict tax relief to the basic rate of tax, it is easy to think that they will not affect basic rate taxpayers. This is not the case, as is illustrated by the example of Ray.

We have referred above to “interest”, but this is a convenient shorthand. In fact, the rules apply to “costs” of a dwelling-related loan and are not restricted to interest: they extend to any return that is economically equivalent to interest, such as premium, discount and returns under sharia-compliant arrangements, and incidental costs of obtaining the loan finance.

No deduction

The restriction applies to the costs of a “dwelling-related loan”. This means any amount borrowed for the purpose of a property business carried on to generate income from dwelling houses.

It does not apply to a business of dealing in property or developing property for sale, only to property letting ones. It is not restricted to loans taken specifically to acquire properties for letting. In principle, the restriction also applies to a loan taken out to acquire a motor vehicle used in the management of a property business, or office accommodation from which a property business is run.

The main effect, though, will be on loans taken out to acquire property for letting.

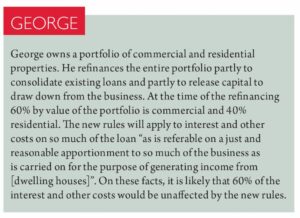

The restriction is specific in its application. First, it applies only to the letting of dwelling houses with an appropriate apportionment where a loan relates in part to a business of letting residential property and in part to some other business, say letting commercial property. See George.

Second, the new rules are expressed not to apply to a property business “carried on by a company” (except where the company carries on the business in a fiduciary or representative capacity). This is the case even for a non-resident company that is liable to income tax on its rental profits.

The new rules do, however, apply to individuals, partnerships and limited liability partnerships. A strict reading of the draft legislation would suggest that a property business carried on by a partnership with even a single corporate member would be outside the new rules because such a business is undoubtedly “carried on by a company”. But presumably this is not the intention and it is to be expected that HMRC would seek to resist such an interpretation.

Third, the restriction does not apply to a loan which is “referable to so much of a property business as consists of the commercial letting of furnished holiday accommodation”. The legislation is silent as to what happens when property ceases to meet the conditions to be “furnished holiday accommodation”. It is likely that the new rules start to apply at that point. The alternative, that a once-and-for-all test is applied at the date the loan is taken, is probably over-optimistic.

Tax reduction

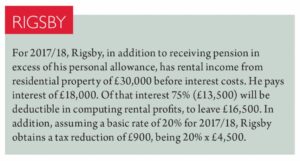

Having denied relief for the costs, the legislation affords a measure of relief by way of a tax reduction. The machinery for doing this is complicated. The tax reduction is broadly tax at the basic rate on the amount for which relief has been denied. But it is limited to tax at the basic rate on the profits of the property business in question after deduction of any brought-forward property losses. Rigsby illustrates the calculation for the first year.

If the property business is carried on in partnership or the property is otherwise jointly owned, each partner or joint owner obtains a tax reduction equal to basic rate tax on his share of the disallowed costs. So if, in Rigsby, the property had been owned jointly by Rigsby and Miss Jones in equal shares, each would have received a tax reduction of £450.

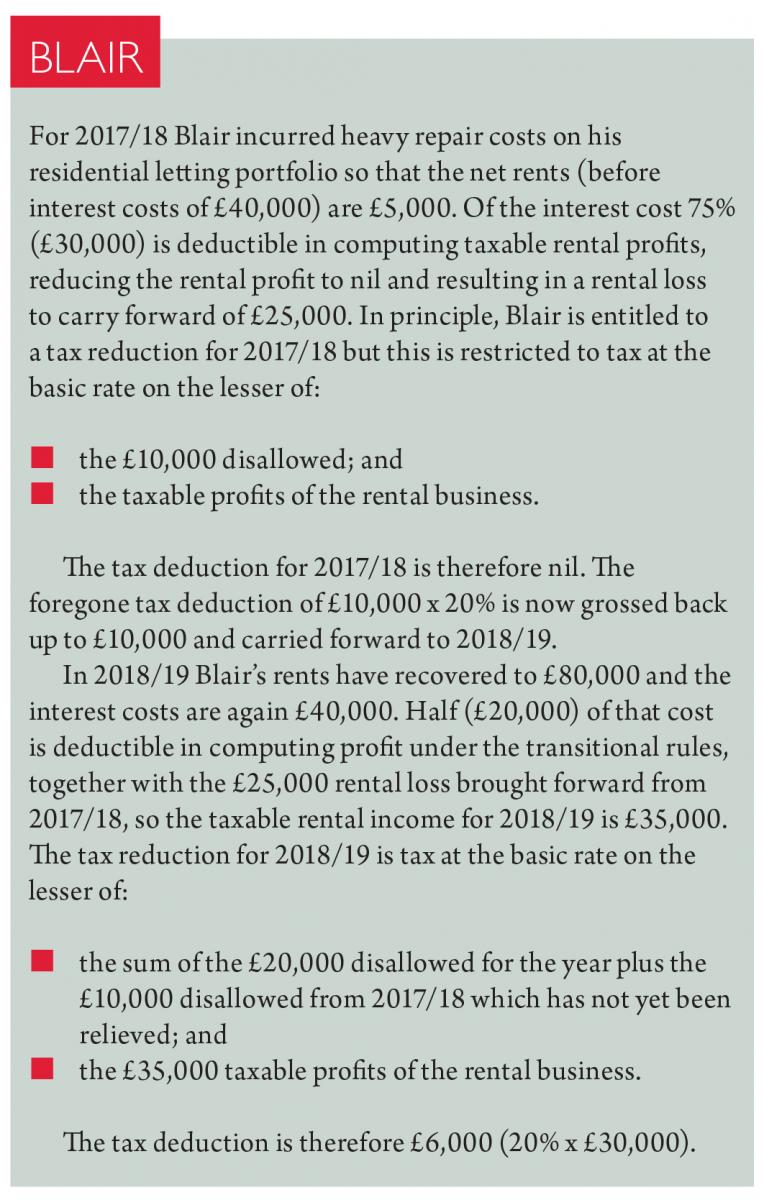

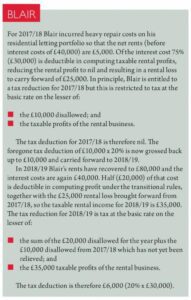

The computation becomes more complicated when the tax reduction cannot be fully used in the year. Blair shows the principles.

There are likely to be deductions from total income in arriving at the amount chargeable to tax, if only on personal allowances. Indeed, in Blair, if it is assumed that Blair has no income other than from property lettings, the availability of a personal allowance will reduce the tax otherwise payable for 2018/19 below the amount of the tax reduction. So the legislation introduces a further restriction, which seems to be broadly intended to restrict the tax reduction to the amount of tax that would otherwise be payable.

The legislation starts by defining “gross finance costs relief” (GFCR) as the amount of the tax deduction to which the taxpayer would otherwise be entitled (in Blair, £6,000 for 2018/19). It then defines the taxpayer’s “adjusted total income” (ATI) as the individual’s total income for the year less savings income, dividend income and personal allowances. In Blair, taking the personal allowance as £10,000, the ATI is £25,000.

The legislation then provides for a restriction of relief if GFCR exceeds ATI. This seems to be a mistake on the part of the draftsman because this would happen only in very unusual circumstances. It seems much more likely that what the draftsman meant to compare with ATI was not the amount of the tax deduction itself but the amount that is multiplied by the basic rate of tax to arrive at the tax deduction. In Rigsby this would be £30,000. When GFCR exceeds ATI, the tax reduction is restricted to:

ATI x (BR x L)

GFCR

where L is the lower of:

- the amount of interest disallowed for the year (plus anything brought forward from earlier years); and

- the rental profit for the year.

Applying this formula to Blair, and assuming that the draftsman has indeed made a mistake in defining GFCR, leads to the sensible result that the tax reduction is restricted to £5,000 – that is, the amount of tax which would otherwise be payable.

The complexity of the computation will be evident even from this relatively simple example. We leave it to the reader to contemplate the effect or more complicated circumstances.

Partnership interest loans

The provisions extend beyond restricting relief for interest as an expense of a residential property letting business. They also apply to interest on a loan taken out to acquire an interest in a property letting partnership.

At present, ITA 2007, s 383 renders such interest deductible in computing the payer’s net income for the tax year in which the interest is paid – it can in effect be offset against total income. Under the new rule, where the property letting partnership carries on the business of letting residential property, tax relief is restricted to relief at the basic rate of tax.

As with the main restriction, the new rule is phased in from 6 April 2017 and apportionment applies where the partnership carries on businesses other than residential property letting. Thankfully, since s 383 contains no carry-forward provision, there is no need to replicate for s 383 the complexity where the tax deduction is not in effect given in the year of payment.

Incorporation

Operating a business through a company has always had the attraction that undistributed profits, including those used to pay down debt, are taxed at company rates of tax. The fact that the new rules do not apply to companies may further increase the attraction of operating a residential property lettings business through a company.

It seems odd that the government should give this incentive to incorporation when the same budget that introduced the buy-to-let changes also brought in measures, such as the increased tax charge on dividends, to discourage tax-driven incorporation.

There are many factors to consider in choosing the right structure.

Structure choice

First, if all profits are being extracted for consumption, the introduction of the new rates of dividend tax from April 2016 will result in the aggregate tax payable on profits routed through a company exceeding the tax payable on profits earned by an individual directly. In some cases this additional tax alone will outweigh any savings from maintaining full tax relief on interest.

Second, the two tiers of capital gains tax on property gains made in a company and subsequently distributed to shareholders may be a serious disadvantage. A property gain of £100,000 would bear tax of £28,000 if made personally, leaving £72,000 net. The same gain made in a company would bear corporation tax of about £20,000 and further tax on distribution of around £26,000, leaving only £54,000 net.

Third, direct and indirect ownership of property are treated differently on death. When properties are owned directly, inheritance tax will be calculated by reference to their values at the date of death (net of debt) but, importantly, the properties will be “re-based” to market value for capital gains tax purposes. Realisation by the executors will therefore not normally incur any capital gains tax charge.

By contrast, when shares in a property-owning company are held, inheritance tax will be due by reference to the value of the shares at the date of death, and they will be “re-based” to market value for inheritance tax purposes. But there will be no “re-basing” of the properties themselves. This may be less of a concern if the property company passes to beneficiaries and continues to be run without substantial changes, but it may add significantly to the tax costs if, on death, the portfolio is sold and the proceeds distributed between beneficiaries.

For an existing portfolio, the costs (including tax costs) of transferring the properties to a company must be considered. If the properties are pregnant with gain, capital gains tax will be an issue unless it is possible to show that the activity amounts to a “business” such that incorporation relief under TCGA 1992, s 162 may be available. If that is the case, the opportunity for a “tax-free” rebasing of the properties is an additional attraction.

In every case stamp duty land tax will also need to be considered. For a partnership or limited liability partnership FA 2003, Sch 15 may offer opportunities for relief but the complex rules will need to be examined carefully.

Start planning now

The changes to relief for costs related to buy-to-let properties are likely to have a profound effect on the economics of many residential property portfolios. Taxpayers should start planning now for April 2017 and beyond.